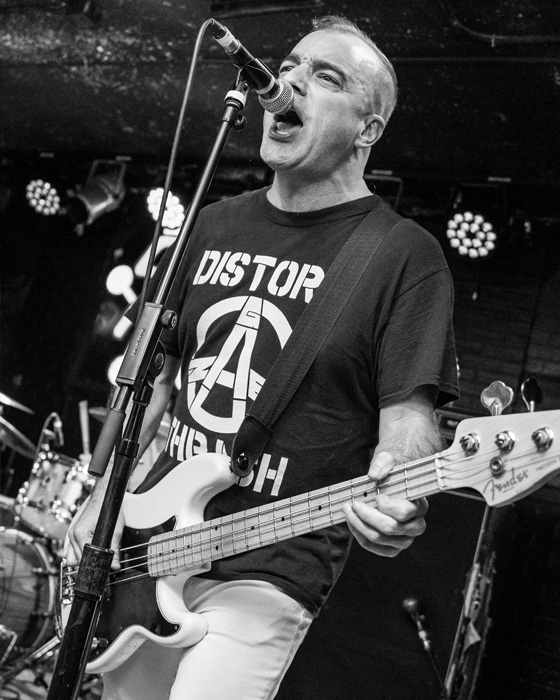

In the opening track of their 2023 release, Famine, Paint It Black vocalist Dan Yemin proclaims in a confrontational snarl, “I’m not staring at my feet, I’ll look you right in the eyes,” and that defiant declaration speaks volumes to the music and message of a band who, over their twenty-two year trajectory, have maintained a fearless commitment to honesty, authenticity, awareness, and activism. By Yemin’s own admission, Paint It Black is protest music, written to inspire and empower as Yemin’s carefully crafted lyrics take sharp aim at the injustices all around us to the beat of pounding drums and ferocious guitars.

Formed in Philadelphia in 2002, Paint It Black has evolved and grown over their time together but remain stalwart in their commitment to speaking truth to power while creating music that holds a mirror up to the world around them. Their latest LP, Famine (2023, Revelation Records), is amongst their best efforts yet, seeing the band forge new roads not only with their sound as they experiment with arrangement and tempo while maintaining the swirling current of carefully tethered chaos that underlies each Paint It Black track, but also in Yemin’s radically honest lyrics that address everything from the infuriating state of America (and the world) to his own personal struggles with parenthood and family.

In anticipation of Famine’s release late last year, Dan took the time to answer a few questions for Today Forever about the new album, the important role music can play in activism and awareness, and what drives him to continue to create with honesty, vulnerability, and, above all else, authenticity.

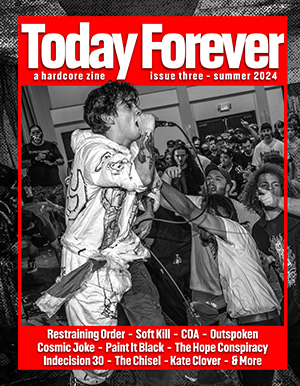

*The original text for this Paint It Black interview appeared in Today Forever Issue 03 in July 2024.

**All text copyright Today Forever 2024, please do not duplicate without expressed editorial permission.

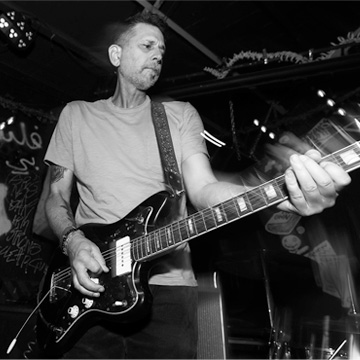

Photos by: Ray Camacho – raymondecamacho.myportfolio.com – IG: punk_monk_ray

Nikki: Paint It Black has emerged from a long period of relative silence to drop a brand new album, Famine, on Revelation records, picking up seamlessly from where you left off ten years ago with Invisible, your last EP on No Idea Records. What made 2023 the right time to release new music? Did you always know the band had another album coming, or was the future not always clear for Paint It Black during your near ten year hiatus?

Dan: I’ve always known we were doing another record, and I’d been slowly writing for what we assumed would be another 7” EP. But, the logistics of doing that are always challenging. Our drummer, Jared, moved to California in 2009, so just getting all of us in a room together takes a lot of planning. Also, he’s a session musician and his schedule is pretty full. In 2019 we got exactly 4 days with him in Philadelphia, which we spent in the practice room just working on songs for 12 hours a day. Then the pandemic delayed everything, and, during that time, Andy and then Josh also moved to the West Coast. For a long time I didn’t feel comfortable getting on a plane because of COVID-19 and my family’s commitments to minimizing risk for our jobs and our kids’ school. Finally, in January 2022 I flew to L.A. and we spent another 3 days locked in Jared’s practice space. It became clear during the next several months that we were beyond the scope of a 7” EP in terms of the amount of material we felt excited about. We’re so deliberate and picky about getting things done exactly the way we want them, so everything takes longer than it might if we had more of a, “fuck it,” attitude. This might make us sound uptight or difficult, but I prefer to think about it as being passionately obsessive about music and the way it’s presented. We’ve developed a tendency to approach releasing and performing music as curators, which we apply to everything from who we play with to obsessing over details of sequencing and mastering, and making sure that design elements are executed exactly how we see it in our heads. On one hand, at this point in our lives we feel like there’s no reason to rush anything, but personally I’m always at war with my own internal engine of impatience.

After an extended break, how hard was it for each of you to “get back on the horse” in order to make a new album and prepare to play shows again? Were you all active in other bands during the break from PIB?

We’re all in other bands and are really busy musically, so “getting back on the horse,” isn’t an issue. Andy has been playing in Ceremony for over 10 years and Jared plays in Boy Sets Fire and Ways Away and fills in on tour as a hired gun for more bands than I can count. Of course, we need to rehearse together so we can crush it on stage. Andy, Josh, and Jared play together in L.A. and I have a strict regimen of screaming in my car to get my throat and breath control in shape. People give me strange looks at red lights, but to be honest that’s something I got used to a long time ago.

Paint It Black has long been known to write both music and lyrics for maximum impact and never shy away from expressing outrage at social and political injustices. As the country continues to spin seemingly out of control, Famine takes direct aim at the mythology behind America, our (often varied) perception of our own history, and a trajectory that seems to veer ever closer to authoritarianism and fundamentalism. Is it always your aim to use your platform to point out the injustices you see in the world? What makes this important to you? Does the band ever experience difficulty over opinions expressed?

Punk and hardcore, for me, has always been closely associated with political awareness. More specifically, I see it as situated within a long history of protest music. I grew up in a very conservative town during the ’80s, the Reagan era, and at the age of sixteen (thanks to an unusually awesome History teacher and just starting to read the newspaper) I was just starting to have an awareness of the hypocrisy of U.S Cold War foreign policy, and to develop an understanding of where I stood on social issues like racism, LGBT rights, and reproductive freedom. I felt pretty alienated and angry a lot of the time, and I’d been listening to the Clash and the Circle Jerks and really focusing on the lyrics. Then a friend took me to my first hardcore show in NYC, which was Reagan Youth. It was a revelation. I felt understood and empowered. I was all in after that. Even if a lot of the bands I loved weren’t always political in the most obvious ways, the message of rejecting mainstream value systems that were oppressive and unhealthy really pulled me in. I really gravitated towards Youth of Today’s criticisms of patriotism and materialism, Gorilla Biscuits’s songs calling out racists and holding themselves (and all of us) accountable for time wasted in front of the television, all of the late ’80s bands who talked about vegetarianism and animal rights. Then there was Crass and their associated bands, and then of course Born Against and other bands that developed around ABC No Rio. Then the ’90s DIY scene was a deep dive into the intersection of the political and personal, opening more critical dialogues about sexism, racism and homophobia and the connection between our consumer behavior and the damage being done by the corporations that we empower with our purchases. All of that was formative and is essential to how I think about making music and writing lyrics. There is no hardcore/punk without all of that. Beyond just pointing out injustices, I’m interested in structural critique, and connecting that to lived experience.

It sounds like the process of writing and recording for Famine took place over several years. When did you originally begin work on the album and what was your writing process like? How did your approach to the album differ this time around considering that half of the band now resides on the West Coast and the other half remains in Philadelphia?

It sounds like the process of writing and recording for Famine took place over several years. When did you originally begin work on the album and what was your writing process like? How did your approach to the album differ this time around considering that half of the band now resides on the West Coast and the other half remains in Philadelphia?

I started writing music and lyrics for Famine as early as 2015. In some ways I’m always writing lyrics, so there’s no real sense of “beginning” and “end,” there. I’m writing music for Paint It Black, Open City, and Lifetime all at the same time so it’s hard to say when we began working on Famine exactly. As I said in answering the first question, we first got together to work on new songs in Philadelphia during the summer of 2019. Then there was a lot of emailing demos and ideas during the pandemic, and we got together again in the beginning of 2022, followed by more emailing/texting of ideas. In the past, we’ve always had a concentrated period of time to really dig into things together, so we had to adjust our process. It can be frustrating but when all is said and done, it’s fine with me because I just have so much less time and flexibility than I did 10 years ago. In the end I think we figured out how to do more with less.

Paint It Black has always been undeniably linked to Philadelphia, and remains that way with Famine. References to the city are woven throughout the album, and half of the band still make Philadelphia their home. How do you think the city of Philadelphia has influenced the band? Has that connection waned at all now that not all band members reside in the area?

Josh, Jared, and Andy all came of age in the Philadelphia hardcore/punk scene and I’ve been here for over 30 years. Collectively, we’ve had so many of our formative musical experiences in Philly, and now I’m raising my own kids here. So, it’s still very much at the root of our musical DNA. When I moved here, Philly was a city that people would usually skip on tour, like just play D.C. and New York and move on. Philly DIY changed that in the ’90s and it became a thriving scene. That history is an essential part of what we are. I think it influenced the lyrics more than ever this time around because I had been reflecting on how living here over the years has impacted us.

The penultimate track on Famine, “Namesake,” seems particularly personal as it delves into the deeply intimate territory of family, a sort of love song from father to son, a tribute that explores the complexities of generational relationships. Then, on the final track, “City of the Dead,” you mention your own father in the line, “I watched my father draw his last breath, mine is a similar affliction.” What made you want to lay yourself so deeply bare on this record? To discuss politics and social outrage are one level of vulnerability, but bringing family into the mix is quite another.

We’re always trying to step things up from record to record, musically, sonically, and lyrically, especially in terms of being open and vulnerable. Honesty is one of the key elements that drew me into hardcore. I’ve always written about personal experiences, but a lot of times it was masked with metaphor and allegory or embedded in political observation. I just wanted to find a way to be more direct about it, to be radically honest and vulnerable, without resorting to being sentimental or self-indulgent. I’ve struggled with being a parent, with being a good husband, and I’ve struggled with loss and grief, and that’s just as urgent as what’s happening politically in the world.

Famine was recorded at The Atomic Garden in Oakland, California and produced, engineered, and mixed by Jack Shirley, a veteran of Bay Area recording and engineering for over 18 years who has worked with a diverse group of talent, including Deafheaven, Gulch, Gouge Away, Joyce Manor, and many more. How did you connect with Jack and The Atomic Garden and what made it the right choice to record Famine there? What was the experience of recording the album like?

Famine was recorded at The Atomic Garden in Oakland, California and produced, engineered, and mixed by Jack Shirley, a veteran of Bay Area recording and engineering for over 18 years who has worked with a diverse group of talent, including Deafheaven, Gulch, Gouge Away, Joyce Manor, and many more. How did you connect with Jack and The Atomic Garden and what made it the right choice to record Famine there? What was the experience of recording the album like?

I first met Jack when he was playing guitar in Comadre. I’ve always liked and respected him, and I had some vague awareness that he had a studio and was a recording engineer. When I found out that he’d recorded the second Baader Brains LP and the Mothercountry Motherfuckers material, and was working on the posthumous MCMF 12”, I started asking him more about his studio and how he likes to work. More recently, Brian and Tobia from Look Back & Laugh have been recording all of their newer bands’ records with Jack, and we have tremendous love and respect for them and their music. The Gouge Away Burnt Sugar LP, the Needles Desesperación EP and the Tørsö Build and Break 7” are some of my favorite hardcore records of the last 10 years, and, of course, I find those Deafheaven records sonically fascinating. All of these were recorded by Jack. The more I knew about him, and the more music I heard coming out of Atomic Garden, the more I dreamed of working with him. We thought it was going to have to remain nothing more than a dream, as I had promised myself I was done traveling out of town for recording. When it became a reality that we had become a bicoastal band and some of us would have to travel no matter what, recording with Jack at The Atomic Garden became the obvious choice. We wanted to be really prepared and efficient, and Andy and I met with him and asked him if he thought we could do it in 3 days. He said, “If you’re really well-rehearsed, and you record live to tape, we can do this with time to spare.” He was right! I was only able to make it for the last day, and I was really nervous that I would throw my voice out and not be able to finish, but it worked out perfectly. It was the first time I ever recorded with a handheld mic, so I felt like we captured that onstage urgency. Usually people set up these very expensive and fragile vocal microphones that you can’t touch or bump into, but this time we just used an SM58, which is the typical vocal mic that people use on stage. We banged things out pretty quickly and had time to make that tape loop that “Exploitation Period,” (the fourth song on the record) is constructed around.

After working with Jade Tree, Fat Wreck, Bridge Nine, and No Idea in the past, what made you choose Revelation Records to release Famine?

It goes without saying that Revelation is one of the labels, along with Dischord, that I associate closely with the time in my life when I went all in on punk and hardcore. From 1988 to 1991 I can still remember where I was when I bought each of their releases, and what I was thinking and feeling when I first dropped the needle and read the lyric sheet. The label is a part of each of our personal histories. So it’s come full circle.

Along with Paint It Black, you and Andy both play in another band, Open City, who are also releasing a new album this fall. When you’re writing music, how do you decide what becomes a Paint It Black song versus a song for another project? Do you purposely keep all of your bands strictly delineated from one another or is there some bleed over?

The decision is usually mine, although there have been a couple of times where I was on the fence about which band a song would work best with, and I checked in with Andy about it. I think of the two bands very differently, and that’s because of the specific creative space we were trying to create for Open City, which had everything to do with the time and place which inspired the band, and the specific group of people I’m collaborating with. Paint It Black has evolved over time so that there’s a lot more potential overlap between the two bands. If Open City suddenly ceased to exist, I’d probably cannibalize two-thirds of those songs for Paint It Black, but the opposite is definitely not true, if that makes any sense. Now that I’m thinking about it, I may not have come up with some of those songs if we’d never started Open City.

Paint It Black has been writing, recording, and playing together for two decades, and each of you are alumni of other hardcore bands, as well. After playing for so long, do you still get the same satisfaction and thrill from making and performing music as you originally did? As you have grown and matured as individuals (and a group) has your relationship to hardcore and music changed as well?

Paint It Black has been writing, recording, and playing together for two decades, and each of you are alumni of other hardcore bands, as well. After playing for so long, do you still get the same satisfaction and thrill from making and performing music as you originally did? As you have grown and matured as individuals (and a group) has your relationship to hardcore and music changed as well?

I was telling someone the other day that I’m feeling just as excited right now as I did 25 years ago when a record was about to drop. When every last word and note and image and design element is committed, and we’re waiting for people to hear it and to react to it, it’s like I’m a kid again looking forward to my birthday or Hanukkah/Christmas. More than ever, I appreciate the privilege of being able to make music while still having a busy career and family life. Playing live is still the best part of all of this, although it is more taxing physically than it used to be. My relationship to hardcore punk is different because I very rarely get to go to shows because I’m hanging out with my family and working. I’m out of the house one night a week for Bitter Branches rehearsal, and that’s about all I can manage unless a friend’s band is coming through, or something ridiculous is happening, like the Unwound reunion tour, 7 Seconds and Negative Approach in the church basement, or taking my daughter to see Alvvays. I put a lot of effort into staying on top of new music, so I feel engaged in that way. My Bandcamp wishlist is hilariously enormous. When I do go to shows I mostly only know the people working the door or doing sound, which can be a little bit alienating, but it’s also exciting seeing the scene that the young kids are building.

Your record release shows for Famine will be taking place in November at The First Unitarian Church in Philadelphia, and you have stated that these will be your last shows of 2023. Do you have more extensive touring plans for the future? As people with jobs, families, responsibilities and obligations that reach well beyond playing in a band, have you had to change your approach to playing shows and touring?

“Touring” at this point means a three day weekend playing out of town, and that’s mostly because of me and my lifestyle. Although I miss being able to travel across the country and play to people far from home, I don’t have any desire to be away from my kids for more than three to four days at a time, and I’m responsible for patient care at work, so outside of family vacations I can’t be away from my office for long stretches of time. So, it’s either playing shows within driving distance or flying in to someplace like California or Chicago or Denver for a few days. I miss being able to leave town for a month with no responsibilities except rent, but that’s as much about missing being 25 as anything else.

As with all things, hardcore, both as music and a scene, has grown and changed a great deal since Paint It Black released their last EP in 2013. How does it feel to be stepping back into the world of 2023 hardcore? Did you have any trepidation as to how Famine, or even Paint It Black itself, will be received in the new hardcore landscape? Has it been a warm welcome back?

As with all things, hardcore, both as music and a scene, has grown and changed a great deal since Paint It Black released their last EP in 2013. How does it feel to be stepping back into the world of 2023 hardcore? Did you have any trepidation as to how Famine, or even Paint It Black itself, will be received in the new hardcore landscape? Has it been a warm welcome back?

I wouldn’t say we’re, “stepping back in,” as Paint It Black, Open City, and Lifetime have all played shows during the pre-pandemic years, Ceremony is still a very active band, and Jared plays in Boy Sets Fire, who are relatively active. Coordinating shows and rehearsals for busy people who live far apart just takes a lot more deliberation and planning. It sounds like a lot of people thought we broke up, but that’s not the case. I feel like the response to the news of the new record, and the new songs, has been overwhelmingly positive. The only thing I’ve observed about the landscape of hardcore having changed is that some bands seem reluctant to risk alienating potential listeners by taking a strong stance on anything. We’re pretty blunt about where we’re coming from politically, which is something that I think may have fallen out of fashion (in some segments of the scene, not others), but again people seem grateful that we make it a priority to address these things.

As we end the interview, is there anything else you’d like to mention or touch on, or any shout outs you’d like to give?

We’re grateful to you for taking an interest in what we’re doing, and for asking good questions. All our love to Revelation Records for supporting this process with us, and of course grateful to everyone who supports Paint It Black and supports underground/weirdo music and art in general.

View this post on Instagram